Living rooms to be seen

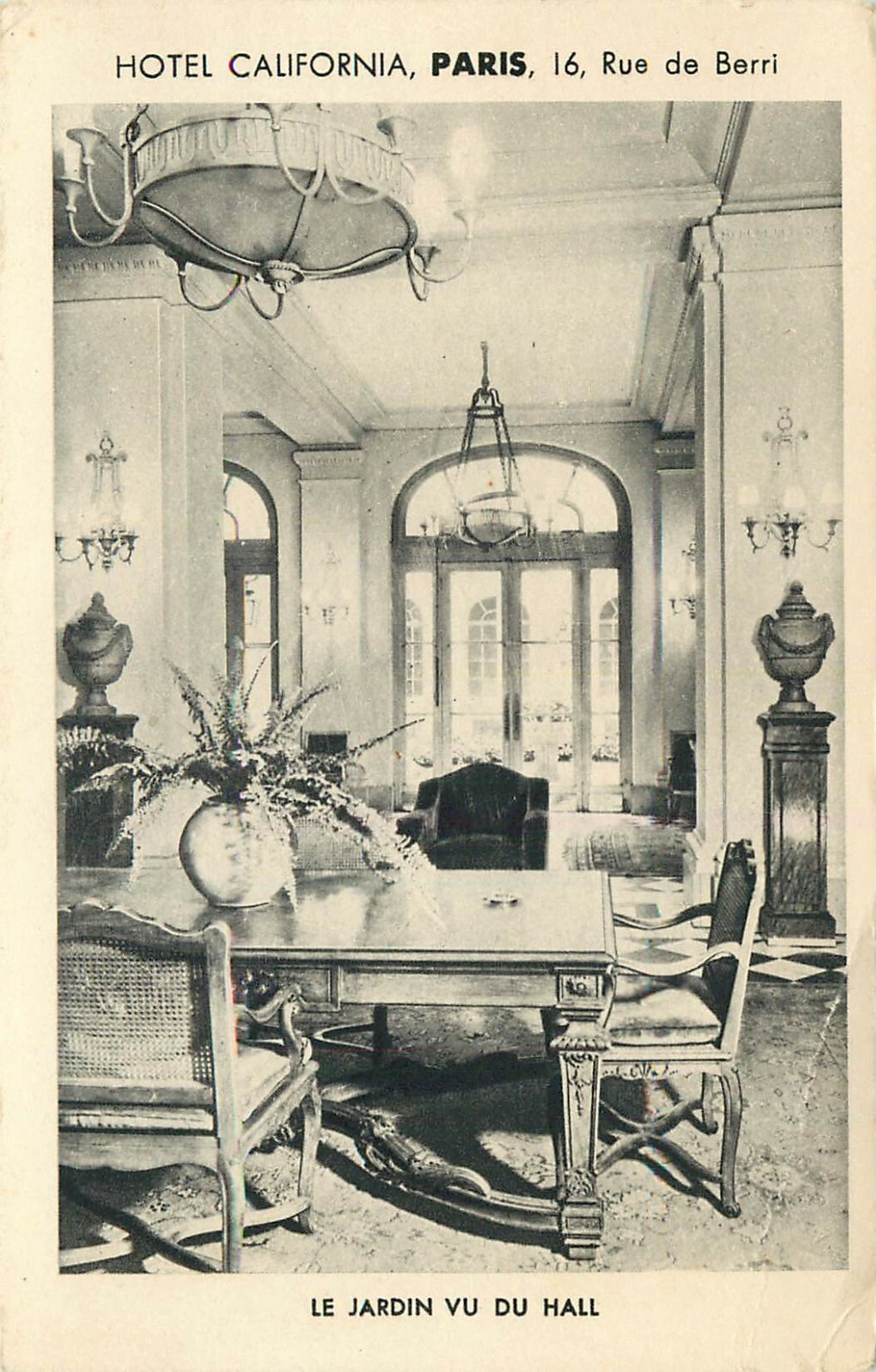

The first time I stepped into the salon of a hôtel particulier in Paris, while working on a renovation, I understood something architectural manuals never mention: for centuries, the living room wasn’t meant to be lived in. It was meant to be shown.

Overdecorated walls, untouched furniture, majestic fireplaces. Nobody actually sat on those sofas or read those books. The salon was a stage—set to receive visitors, display taste, culture, and social standing. Conversations about art or politics followed strict scripts. Domestic life was not yet intimate.

These salons were born in Louis XV’s France, at Versailles, as liminal spaces between public and private life. For generations, having a salon signaled belonging to an educated elite.

Today, my clients often say: “I want a living room you’re not afraid to touch.” In other words: lived-in, not displayed. That’s the true paradigm shift.

The parlor of good manners

With the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the bourgeoisie, the living room entered middle-class homes. In England, they called it the parlor, and its function was clear: maintain appearances.

During a renovation of an old flat in Barcelona, we found a living room that had barely been used. Period furniture under covers, an impractical chandelier, everything untouched. The owner told me the space had been reserved for “real guests” for over thirty years. Not even the children went in.

That museum-like idea of the living room still exists quietly in many homes.

In the Victorian era, the living room was a kind of domestic theatre—used to show what you had, not who you were. Many flawed design habits today—rigid layouts, illogical orientations—stem from this obsolete model, still haunting us unconsciously.

When the living room came alive

The real shift came in the 20th century—not from architectural innovation, but from cultural change.

In post-WWII America, a new concept emerged: the family room. George Nelson, designer and co-author of Tomorrow’s House, described it as a “room without a name.” No longer a formal salon, nor a music or dining room—it was simply where life happened.

In our recent projects, the living room is no longer enclosed—it becomes the home’s center of gravity. A place of convergence. Often flowing into the kitchen, open to porches or patios, furnished with comfort and flexibility. Because today, life doesn’t distinguish between cooking, resting, working on a laptop or watching a movie with your children.

This kind of room—open, versatile, free from hierarchy—is a direct heir to the American family room. A space designed for coexistence, not performance.

Photo: Hôtel de Soubise Salons, Paris

The modern living room: fluidity and freedom

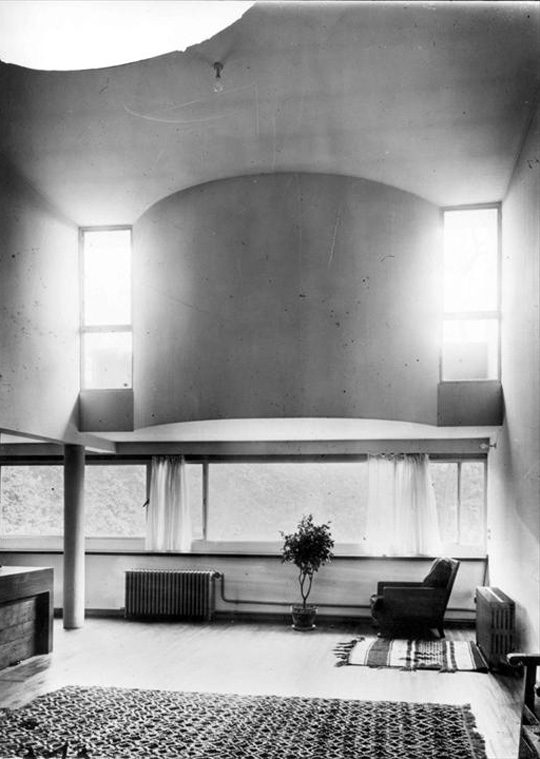

When I studied architecture, one of the most powerful revelations was Le Corbusier’s free plan. In the Maison La Roche, for instance, the living room no longer has traditional walls—it opens to the ramp, to the gallery, to the void. Everything becomes circulation, continuity, air.

That concept still informs many of our designs. It’s not about tearing down walls arbitrarily—it’s about understanding how people actually live. When someone tells me “I want a house where you can breathe,” I know that living room won’t have doors, symmetrical furniture, or a central ceiling lamp. It will have flows. Connections. Possibilities.

Even small flats can achieve this. I’ve renovated 60 m² homes in Barcelona where simply shifting a hallway wall or cutting an opening between the kitchen and living room transformed how people lived. The living room stopped being a compartment—it became a real place of togetherness.

What if the living room disappears?

In recent years, younger clients openly tell me: “we don’t want a living room.” They want a large kitchen-dining space with a sofa tucked in. Or a continuous space with layered atmospheres.

And I understand.

Homes are getting smaller. Life moves faster. Formal entertaining is nearly extinct. There’s no need to impress guests anymore.

The living room, as a distinct space, is fading.

But that doesn’t mean it’s disappearing. It’s evolving. It no longer needs four walls to exist. It can be a corner by the fireplace, a sofa facing the light, a bench under a window, a yoga mat.

The living room is wherever you can be—with others, or with yourself.

The living room is not a room type. It’s a way of life. It has been stage, domestic throne, playroom, retreat, showroom, and now, a laboratory of how we inhabit space.

As an architect, my job is not to impose a definition of “living room”, but to listen to how people want to live—and translate that into space.

And that translation, however abstract it may seem, begins with concrete things: where the light falls, what you see from the sofa, how a conversation sounds, where you rest your cup.

That’s where the living room truly begins.

Photo: Maison La Roche,, Le Corbusier (Ferdinand Choffray)

The Living Room as the Heart

The emotional center of the home

“There is no home without a place to pause, to breathe, and to share. A well-designed living room is exactly that.”

Whenever a house design begins, there’s a question I ask myself early on—often before drawing a single line:

Where does this home pulse?

I don’t mean its structural axis, solar orientation, or even its circulation flow. I mean that space that quietly organizes everything. Where people end up sitting without planning to. Where the meaningful moments happen. In many homes, that place is the living room. But not just any living room—one with a soul.

Spaces that pulse from the center

One of the most influential books I read early in my career was A Pattern Language by Christopher Alexander. Pattern #129 is titled “Common Areas at the Heart”, and its premise is simple but powerful: if a group of people doesn’t have a natural central place to gather, that group will fragment. In a house, that place should be the living room.

I recall a project, a house among pine trees with sea views. I could have oriented the living room southward, toward the pool. But instead, we placed it at the core of the house—an enclosed interior courtyard of sorts, protected and enveloping. From there, you could reach the kitchen, the bedrooms, the porch. Everything revolved around it.

And the result wasn’t just functional—it was emotional.

Months later, the client told me:

“We always end up here, without even thinking about it. It’s like the house pulls us toward this space.”

That’s a good living room—one that doesn’t impose itself, but gently organizes everything around it.

Photo: Lightwell Residence (FEM).

Loos and the art of suggestion

In his 1930 Villa Müller, Adolf Loos developed a spatial concept that goes beyond floor plans: the Raumplan. It’s not about stacking rooms on flat planes but articulating spaces by height, function, and time of day.

The main living room—a double-height space with tall windows and an austere fireplace—is connected to surrounding areas by small thresholds, steps, and level shifts.

I’ve tried to echo this approach, at a domestic scale, in several single-family homes. In Lightwell Residence, for example, we placed the living room on a split level—just a few steps between the kitchen and the garden. That slight shift gave it a distinct presence. It wasn’t the largest or brightest room, but it was the one that most invited people to linger.

Loos also cared deeply about atmosphere. His interiors were never white or minimalist. He used dark woods, thick fabrics, dim lighting—because he believed a living room should suggest intimacy, not spectacle. That idea still guides me when a client asks for “a space to disconnect.”

Sinking to connect

Another fascinating precedent is Eero Saarinen’s Miller House (1957), in Indiana. It introduced one of the most radical living room gestures in 20th-century architecture: the conversation pit.

What was it? A portion of the living room lowered by several steps, wrapped in continuous seating—a sunken stage for eye-level conversation and genuine connection.

The rest of the house is all horizontal lines and visual continuity—but it’s this gesture of sinking that gives it character.

In a house we designed in Cardedeu, we didn’t go as far as creating a full pit, but we did lower the living room 40 cm below the kitchen and dining area. That single move achieved several things:

• It separated zones without partitions

• It gave more height to the lounge area

• And it created an emotional effect: the act of descending subtly altered the rhythm of movement

That change, however small, transformed how the space was used. I learned this partly from Saarinen, and partly from observing how people behave.

If the living room is flush with everything else, it becomes a corridor.

If it’s slightly sunken, it becomes a destination.

Photo: Villa Müller, Adolf Loos (Creative Commons)

It’s not just layout

In many of my projects, the living room isn’t placed at the geometric center of the plan, but it holds the symbolic one. It doesn’t need to be “in the middle.” What it needs is a gesture: a shift in scale, in light, in materiality.

In the Ceramic Patio House in Granollers, for instance, the living room occupies the core of the house as a double-height void, pierced from above by a skylight that filters daylight like a vertical well. The space is wrapped by ceramic surfaces and connected on all sides, yet it feels at once sheltered and expansive.

The result is a place that invites reading, conversation, stillness. It wasn’t conceived to impress, but to resonate with everyday life.

And that kind of presence doesn’t reveal itself in renders or catalogues—you only understand it when you step inside. For me, those are the gestures that distinguish a house that simply works from one that carries a soul.

Emotion is designed

We often think emotion just “happens” in a space—as a happy accident. But that’s not true. Emotion is designed.

Through proportion, light, material, sequence.

And if the living room is the emotional core of the home, it requires that level of intention.

It’s not enough to place a big sofa and a coffee table.

You have to consider how winter light enters. What you see when you’re seated. How sounds are absorbed.

A good living room has as much to do with scale as with resonance.

And that’s what I strive for in every project—beyond style, budget, or trend.

A living room is not just where we sit.

It’s where the house comes together emotionally.

Where unscripted things happen: a conversation, a pause, a reunion.

And that’s why, regardless of its size or position, I believe every well-designed living room must act as a heart.

Not the loudest part of the house—but the most alive.

Photo: Ceramic Patio House (FEM).

Modernity and the New Domesticity

“In architecture, freeing a space doesn’t mean leaving it empty. It means giving it back its movement.”

For a long time, the living room was a closed set: four walls, one door, a central lamp, and symmetrical furniture laid out as if awaiting a distinguished guest. But in the 20th century, that understanding of the home began to crumble. New materials emerged. But more importantly, new ways of living.

The living room stopped being a room. It became an idea.

The free plan as domestic revolution

There are a few concepts every architecture student carries forever. One of them is the free plan. Le Corbusier formulated it as one of his “Five Points of a New Architecture”, but what truly changed things was how he applied it to the home.

In projects like the Maison Cook in Paris, the living room rises above the street, surrounded by ribbon windows and continuous light. But its power isn’t in the aesthetics—it’s in the absence of boundaries. The living room doesn’t start or stop anywhere. It extends. It blends into the terrace, into the garden, into the air.

That changed us. Not just as architects—but as dwellers.

I remember one living room we designed where the client insisted: no walls. Not even low partitions or sliding panels. They had only one request:

“I want to see the sky when I eat breakfast, and keep the fireplace in view when I read.”

We made it happen with a non-hierarchical plan: living, dining, and kitchen shared one continuous surface. No breaks. The space was defined not by walls, but by light, rugs, gestures, and furniture. And it worked.

It wasn’t just another room in the house. It was a field of experience.

Photo: Maison Cook, Le Corbusier.

Mies and radical transparency

Le Corbusier freed the plan. Mies van der Rohe went further: he freed the skin.

In the Farnsworth House, the living room sits inside a glass box suspended above the landscape. Everything is continuous. No walls. Barely any doors. The living room isn’t built—it simply happens, carried by the spatial flow.

Of course, that radical gesture came at a cost. The house has often been criticized as almost uninhabitable—too exposed, too fragile, more manifesto than home. And yet, that is precisely what makes it so powerful: the courage to push domestic space beyond convention, even at the risk of discomfort.

Which raises a question we ask often in our own work:

How do you define a living room—without enclosing it?

We’ve designed spaces with no walls at all, and yet you can still feel precisely where the “living” begins, where it merges with the kitchen, where it shifts toward the garden. We define it with textures, orientation, light transitions, floor changes.

You don’t need to close a space for it to exist. You just have to give it identity.

Furniture as architecture

One of the key lessons from Le Corbusier and Mies is that furniture isn’t an accessory. It’s architecture.

In the Farnsworth House, furniture doesn’t fill space—it draws it. In Le Corbusier’s Lake House, a low sofa placed near a curved wall defines a living room without any enclosure.

In many of our own projects, furniture serves this same purpose: structuring the void. An L-shaped sofa can articulate boundaries more subtly—and more effectively—than a built wall. A jute rug, a bench below a window, a low bookshelf—they all become architectural tools when conceived that way.

This is especially useful when space is tight. Instead of dividing, we suggest. Instead of enclosing, we compose. The living room isn’t a box to fill. It’s a sequence to orchestrate.

And when the composition flows, the space feels bigger—without growing at all.

Photo: House Na. Sou Fujimoto (Iwan Baan).

Movement and Stillness

One of the constant challenges in open-plan design is avoiding the corridor effect. Too often, living rooms without walls become little more than circulation zones: everyone passes through, but no one stays.

The key is to introduce anchors —elements that stop the eye, slow the pace, and invite presence. These can be as simple as a low sofa slightly off-axis, a reading chair turned toward the light, or a rug that defines a territory within the flow. What matters is not the object itself, but the way it claims attention and gives people a reason to pause.

Without these anchors, the living room dissolves into transit. With them, movement becomes rhythm and stillness becomes possible. A true living space emerges not from its size, but from its capacity to hold both.

Dissolving Boundaries

One of the most enduring lessons from Le Corbusier and Mies is that a living room can act as an extension of the landscape.

Not metaphorically—literally.

The secret lies in dissolving boundaries with carefully chosen gestures: frameless glass that erases thresholds, floors that continue outward as terraces, porches conceived as roofless rooms, gardens that enter the interior through carefully framed views. These are not decorative devices but spatial continuities—ways of making nature part of the room itself.

When this happens, the living room ceases to be defined by walls. Its limits are set instead by light, by the horizon, by the slow rhythm of the weather. At that point, architecture withdraws. It becomes atmosphere. A living room no longer as an object, but as a pause between body and world.

Liberating the living room doesn’t mean making it bigger. It means opening it to life.

Le Corbusier and Mies taught us that comfort doesn’t come from enclosure, but from the relationships between things: between light and matter, between void and rhythm, between inside and out.

As an architect, I’m still searching for living rooms that aren’t just spaces to occupy—but spaces where something happens.

Something subtle, but real.

Photo: Koshino House, Tadao Ando (MoMA).

The Living Room as a Cultural Scene

“Every home has a voice. And that voice, more than architecture, is defined by the objects that live in the living room.”

One of the most revealing moments in the design process doesn’t happen in front of the drawing board. It happens when I first step into a client’s home.

I observe how the books are arranged, whether the blankets are folded or carelessly thrown, whether the objects on the shelves are memories, gifts, or fillers. And most of all, I watch how people sit. What space they occupy. How they look around. The importance they silently assign to the living room—without realizing they’re saying everything through their posture.

That’s when you begin to understand the kind of domestic culture present in a home.

Because the living room isn’t just architecture.

It’s a material staging of how we live.

Lina Bo Bardi and the living room as cultural crossroads

There’s an image that has stayed with me for years: the living room in Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro, São Paulo, 1951.

A luminous, elevated space open to the garden. But what makes it truly special is not its architecture—it’s what it contains.

Renaissance sculptures coexist with African masks, Brazilian folk art, religious icons, furniture designed by Bo Bardi herself. Everything mixed with ease. No hierarchy. No justification.

That living room is a declaration of values.

Bo Bardi wasn’t interested in decorating. She wanted to inhabit with meaning. She believed in an architecture that doesn’t exclude the everyday—but embraces it. For her, the living room was where personal and collective cultures intertwine.

A client once brought in boxes of inherited objects: an old radio, ceramics from their mother, an African tapestry from a trip. Their only request:

“I don’t want a modern living room. I want mine.”

And that’s what it became.

Not because we imposed a style, but because we designed a space where those pieces could breathe.

The living room as an open biography

Sometimes I feel there are two kinds of living rooms:

- Those that show what people own

- And those that tell who they are

I’m always more interested in the second. And that has implications for how we design.

A living room conceived as biography cannot be neutral.

It needs places to display—and places to conceal. Open shelves and closed cabinets. Surfaces that invite the placement of objects—not the kind that must always be cleared for a photoshoot.

In several projects, the starting point was a single, meaningful piece: a family bench, a handmade bookcase, an inherited armchair.

Instead of hiding or replacing it, we made it the narrative center of the living room.

And something curious happens when the space respects such an object: the whole room reorganizes around it. The atmosphere changes. The space gains weight.

It’s as if the architecture recognizes the story it holds.

Photo: Casa de Vidro, Lina Bo Bardi (Maira Martines).

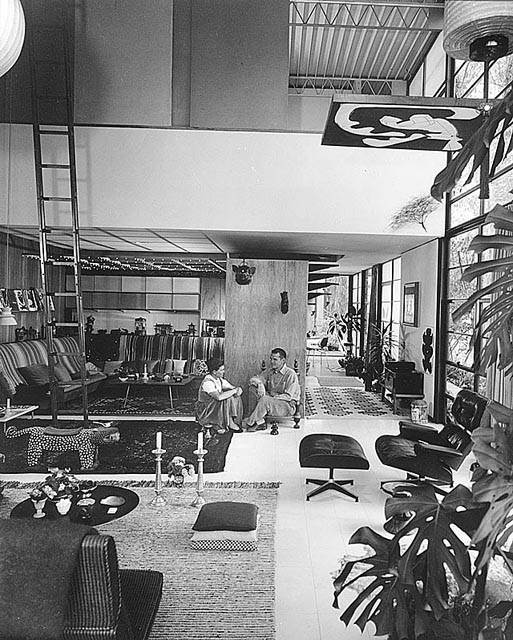

Charles and Ray Eames: the art of intelligent accumulation

Few houses have inspired me as much as the Eames House in California, designed in 1949. Its living room is a celebration of objects: folk art, photos, toys, textiles, books, chairs of every kind. At first glance, it looks chaotic—and yet, everything is exactly where it belongs.

Ray Eames was known for shifting pieces by centimeters until visual balance was achieved.

It wasn’t decoration.

It was vital composition.

To me, that space isn’t just an aesthetic reference. It’s a philosophy of living. A way of showing that comfort is not incompatible with density, and that good design can coexist with real life.

“I want a living room that feels lived-in—but not cluttered.”

That sentence captures a very contemporary dilemma:

How can we design spaces that welcome objects without becoming storage rooms?

How do we make the personal feel intentional, not improvised?

The living room as an open biography

Sometimes I feel there are two kinds of living rooms:

- Those that show what people own

- And those that tell who they are

I’m always more interested in the second. And that has implications for how we design.

A living room conceived as biography cannot be neutral.

It needs places to display—and places to conceal. Open shelves and closed cabinets. Surfaces that invite the placement of objects—not the kind that must always be cleared for a photoshoot.

In several projects, the starting point was a single, meaningful piece: a family bench, a handmade bookcase, an inherited armchair.

Instead of hiding or replacing it, we made it the narrative center of the living room.

And something curious happens when the space respects such an object: the whole room reorganizes around it. The atmosphere changes. The space gains weight.

It’s as if the architecture recognizes the story it holds.

Photo: Eames House, Charles & Ray Eames (Library of Congress).

Furniture with history

Contemporary design—fueled by Pinterest and similar platforms—has bred a kind of anxiety around the “perfect” living room. Everything must match. Coordinate. Feel harmonious. But sometimes that kills the soul of a space.

We’ve started lately embracing the existing furniture of our clients. Not imposing, but curating. Sometimes the pieces are wildly mismatched: a rustic rocking chair, a glass table, a painting that clashes with everything.

But when we treat them with spatial, luminous, and narrative respect, those objects take on a new meaning. The living room becomes less a showroom—and more a dialogue between things.

And our job, as architects, isn’t to silence that dialogue.

It’s to build the stage for it.

Material culture isn’t accumulation—it’s identity

Designing through objects isn’t about filling space. It’s about listening to what the space already knows about those who live there.

Sometimes it’s a lamp from the 1970s. Other times, a wicker armchair from a grandmother. Or a blank canvas, waiting for life to unfold.

In all cases, the living room should allow those things to speak.

When that happens, the living room is no longer something to be shown.

It becomes something to be told.

And when someone walks in for the first time, they don’t ask who designed it.

They ask about the story.

The living room is not just a place to be.

It’s a place to be with the things that matter.

Designing through material culture is not nostalgia or trend.

It’s a way to ensure that architecture doesn’t erase life—but embraces it.

As an architect, I’m increasingly drawn to that place where design leaves room for the unexpected.

Where each object finds not just a place—but a voice.

Photo: Zig-Zag Hill House (FEM)

Emotional and Intimate Spaces

“Some living rooms simply work. Others, somehow, move you. You don’t know exactly why—but you feel different when you’re there.”

You can design a living room that is perfect in proportion, light, and layout.

But if it doesn’t stir something—if it doesn’t produce a certain inner stillness—something is missing.

Over the years, I’ve learned that the most memorable spaces are not just functional. They’re places that generate a sensation that’s hard to explain: calm, presence, introspection.

Rooms that are not only inhabited—but transformative.

Barragán and the living room as interior experience

Luis Barragán spoke of emotional architecture. His houses in Mexico didn’t seek to impress with technology or gleam with luxurious finishes. They aimed to touch the soul.

And in his living rooms, that’s unmistakable. Thick walls. Deep colors. Filtered light. High ceilings. And that rare architectural silence that’s so hard to design. His living rooms aren’t open or transparent. They’re boxes for contemplation.

In them, materials like wood, plaster, and stone don’t decorate—they contain. Light doesn’t illuminate—it reveals. Furniture is sparse, arranged not out of functional need, but spiritual intent.

The lesson is clear: when designing a living room, it isn’t always about opening outward. Sometimes, it means closing in—creating surfaces that hold, filtering light so that it arrives indirectly, even vertically, like a quiet presence. A single shaft of soft daylight can give a room more spirit than a panoramic view.

Designing for emotion doesn’t require spectacle. It requires restraint, proportion, and the courage to let silence be part of the architecture.

The sacred in the everyday

There’s a fine line between the domestic and the sacred.

And some living rooms—without being temples or shrines—sit precisely on that threshold.

The key lies not in decoration, but in proportion and atmosphere. A single artwork, a textured wall, or a shaft of light can carry more weight than any showpiece. When scale and light are handled with care, the room doesn’t demand attention—it quietly gathers presence.

A well-designed living room doesn’t say “look at me.”

It says “feel me.”

Photo: Casa Estudio, Luís Barragán (CreativeCommons)

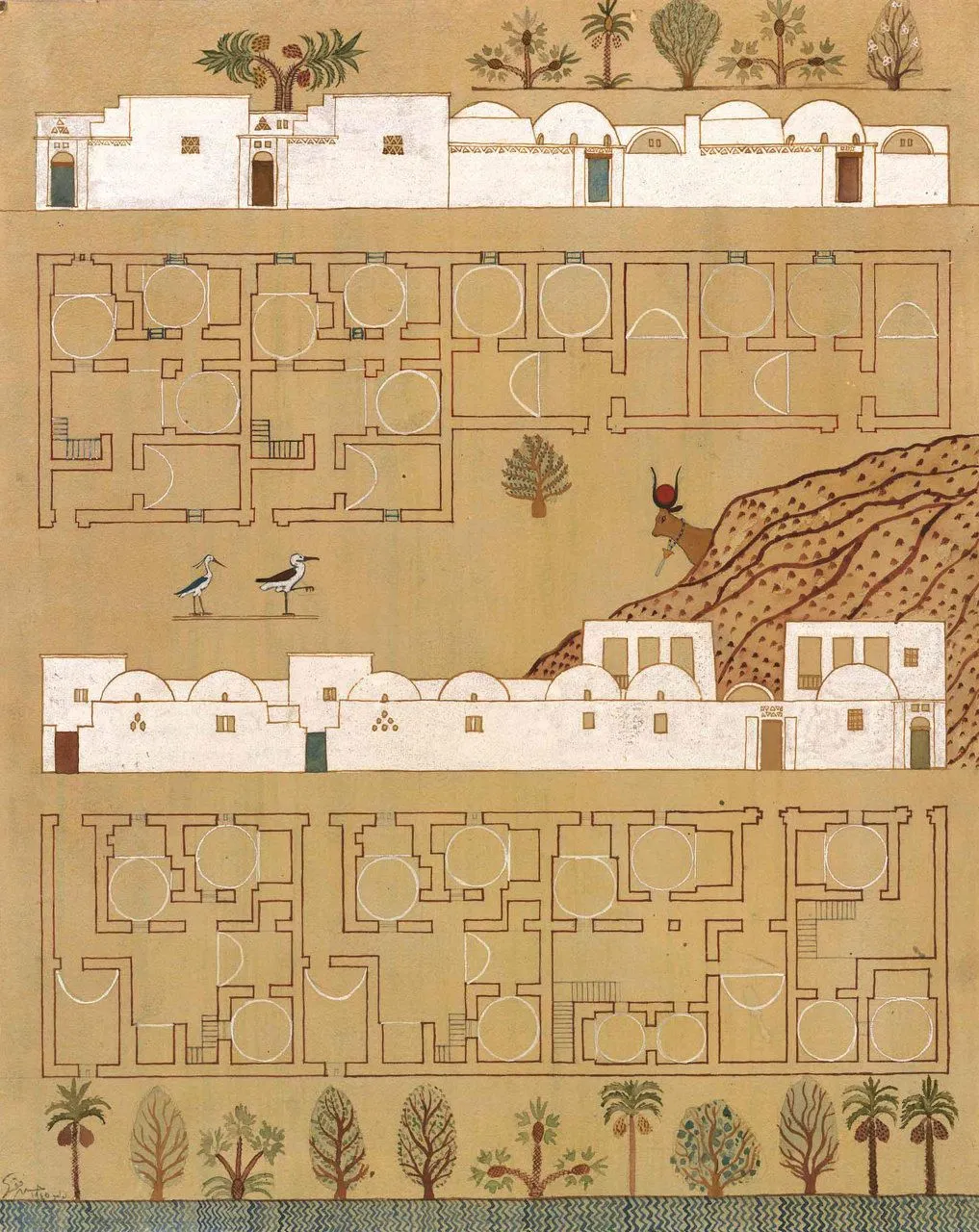

Fathy and the living room as ancestral culture

Hassan Fathy remains a singular voice in modern architecture: an Egyptian visionary who reclaimed vernacular forms to create buildings that were both deeply rooted and unmistakably contemporary.

In his homes for hot climates, the living room wasn’t open to the outside. It was cool, internal, enclosed by thick walls and breathing through a patio.

His reference was the qa’a—an Arab typology of central hall, slightly sunken, with raised sitting areas on the sides. A living room that organizes the house, while still allowing privacy and rest.

Not every living room needs to face outward. Sometimes the most powerful gesture is to protect it—to place it away from the façade, to let it open toward an inner courtyard, or to create a space that looks inward rather than toward the world.

Designing for rest often means designing for shelter. A living room doesn’t always need a view to be alive. Sometimes its strength lies in its ability to hold stillness.

Emotion without spectacle

Some living rooms are designed for an immediate wow effect.

That has its place.

But the most enduring spaces don’t impress in two minutes—they reveal themselves slowly.

A living room should move you after twenty minutes, not in the first two. It should be the place where, once seated, something inside you quiets down. A pause. A deceleration.

That quality doesn’t come from panoramic windows or oversized sofas. It comes from proportion handled with precision, from materials that absorb sound, from light that shifts with the hours. And above all, from the courage to resist filling the room with objects.

True emotion isn’t born from form.

It arises from atmosphere.

Photo: Hassan Fathy. New Gourna Village, Luxor.

Formal Reinventions

“Some forms may look decorative, but in truth, they are ideas. And some living rooms, with just one gesture, transform the way we inhabit them.”

It’s not always about inventing something new.

Sometimes, it’s just about looking differently.

In living room design, some decisions have marked true turning points: stepping down a few levels, rotating a sofa, breaking the symmetry. Small formal reinventions that forever shifted how we conceive the contemporary living room.

Living Rooms Without a Name

George Nelson was already saying it in 1945:

“We need a room without a name.”

Not a formal living room. Not a study. Not a dining room.

But a flexible space, without fixed labels.

That concept is more alive than ever.

Many clients no longer want a “living room” in the traditional sense.

They want a place where everything can happen: breakfast, work, playtime with children, yoga, Netflix, dinner with friends.

As architects, that means we must rethink boundaries.

Often, the living room no longer starts with a sofa, but with a sequence of possible scenarios:

A floor cushion.

A low shelf that becomes a bench.

A movable reading lamp.

A rug that defines territory without enclosing it.

Flexibility as Standard

A living room does not need a single focal point. It can exist as overlapping zones: a place to sit, a place to read, a place to face the garden.

When no hierarchy is imposed, the space adjusts to the rhythm of life. The room can be all of these places—or none of them—depending on the moment.

This kind of design is less dramatic, but more honest. And ultimately, more real.

Photo: Maison Bernard, Antti Lovag (CreativeCommons)

The Future (and Crisis) of the Living Room

“The living room has always been the heart of the home. But… what if the heart has moved?”

This question isn’t provocation for its own sake.

It’s real.

In recent years, we’ve received more and more commissions where the living room no longer exists as a classical concept—not as a separate room, nor as the architectural centerpiece.

Not because people no longer care about comfort.

But because the way we live has changed.

The Living Room Is Morphing

Today, very few of us host formal guests.

No one’s saving the good china in display cabinets anymore.

What we want is a space that does many things at once.

And if that means sacrificing the idea of a “living room” to make the kitchen island bigger, or to gain a home office—they’ll do it.

So is this the death of the living room?

Not quite.

It’s its transformation.

Living Rooms Without TV

Another growing trend: the living room without a television.

More and more families are asking for layouts where the TV is not the focus—or not even present at all.

That changes everything.

The living room stops being a domestic cinema and returns to being a social space.

We design corners for reading, for playing, for simply being in silence.

Spaces where you don’t have to be entertained.

Just… be.

Photo: aHouse on a curved road, Kazuo Shinohara (Koji Taki)

The Living Room Is Not Dead. It’s Returning to Its Origins.

Paradoxically, none of this is entirely new.

The living room was originally conceived as a space for conversation, for pause, for connection.

And what we’re seeing today is a return to that.

But this time, without the stiffness of the past, without the Victorian formality or the staging of glossy interiors.

The new living room doesn’t always announce itself.

But when you find it, you feel it.

Because something very simple happens:

You want to stay.

We’re not witnessing the death of the living room.

We’re witnessing its liberation.

The living room is no longer a space with a name.

It’s an experience without a label.

And that, as an architect, doesn’t worry me.

It excites me.

Because designing a good living room is no longer about following a typology.

It’s about listening to how people live, and creating a place where that life takes shape.

Photo: Caruso St John, Brick House (MACK, 2022)