Light as Cultural Material

In architecture, light is never neutral.

Roman light is not Islamic light. Greek light is not Japanese. Each culture has shaped its own relationship with sun, shadow, and time.

Here—Barcelona, the Mediterranean basin, Southern Europe—this relationship is both climatic and symbolic.

Think of the whitewashed houses in Axarquía, the dense casbahs of North Africa, or the excavated homes in Menorca. These aren’t just shelters from heat—they build an interior world where light is invited, not controlled.

One of the most fascinating homes I’ve ever visited wasn’t in a book. It sat half-buried in the rocky hills of Les Garrigues: mud walls, no windows to the street. Light entered through a narrow patio, bounced off a whitewashed wall, and slipped through a slit opening. The result wasn’t darkness—it was a vibrant, serene clarity.

That house—probably built without an architect—understood light better than many contemporary buildings.

Light as Everyday Emotion

We often speak of natural light as if it were constant. But in truth, it changes every minute. And a well-designed house should pulse with those changes.

The soft morning light that filters through a screen is nothing like the bold midday glow, or the golden wash of evening light grazing textured floors. Winter light—scarce and oblique—is more dramatic still.

In a recent project, we chose not to place windows on the main façade. Instead, we designed a narrow white patio with an inclined skylight. Throughout the day, that space performs a quiet choreography: at 8 am, a warm stripe appears in the kitchen; by 2 pm, the back wall of the living room glows like a theatre set; at 6, light bounces up from below and turns the ceiling into a shimmering surface.

Months later, the family wrote to tell us their daughter had given each time of day a name based on the patio’s light. That’s when we knew the design had worked.

A View from Here

In our practice across the Mediterranean, light is not something to be captured, but something to be framed, softened, filtered.

The Catalan masía achieves this with thick walls and deep-set openings. The Andalusian house, with patios that distribute the day. The whitewashed Greek homes, with minimal windows and indirect orientation. The Roman villa, with its central impluvium and enveloping penumbra.

What these architectures share is not a style, but a deep understanding: light cannot be possessed—but it can be invited.

And that, ultimately, is what we do: we invite light to be part of domestic life. Not as a fleeting guest, but as an active presence in the everyday experience.

Rome and Greece: Light Through the Void

“In ancient architecture, light was not a resource—it was a structure. It didn’t just illuminate spaces: it ordered them.”

There’s an image I’ve always found fascinating. In many Roman houses, right below the impluvium, light would enter from above like a slit in the sky. It wasn’t a window—not even a skylight—but a controlled, vertical, precise cut.

And everything—the atrium, the corridors, the adjacent rooms—was organised around it.

In times when façades were thick and the outside was more threat than promise, light was brought inward. It was guided. It was awaited.

The Void as Structure

In the Roman domus, light was not peripheral—it was axial. The patio wasn’t hidden behind the house—it was the centre. A source of air, clarity, and stillness.

This void—the impluvium, the peristyle—was not just functional. It was symbolic. The sky was framed by the house. The interior was arranged around the exterior.

A paradox that still holds power today.

In a recent project, we recovered this idea—not by copying it literally, but by designing a deep, undecorated central patio. From the living room, there was no view of the garden or the landscape, only the sky. And that was enough.

The owners told us the house felt like a refuge. I believe it was because light didn’t come from outside, but from within. Because the centre wasn’t a piece of furniture—it was an emptiness.

Photo: House of the Silver Wedding, Pompei (Bridgeman)

Filtered, Not Exposed

In our practice across the Mediterranean, light is not something to be captured, but something to be framed, softened, filtered.

The Catalan masía achieves this with thick walls and deep-set openings. The Andalusian house, with patios that distribute the In many ancient Greek houses—especially in Delos or Priene—the interior patios were smaller, more enclosed, but served the same purpose.

They sheltered from direct sun, wind, and heat—while offering soft, constant illumination.

White stone returned light as a calm reflection. Shadows weren’t absence, but pauses.

There was no drama in that architecture. There was continuity.

And in many Mediterranean homes today—whether we’re aware or not—that legacy lives on: in patios ringed by galleries, in eaves extended with fabric, in the way a wall pulls back just enough to admit morning light, but not the afternoon.

Proportion and Orientation

Vitruvius wrote that a well-designed house was one in balance with the climate and the movement of the sun. What we now call energy efficiency, they already understood two thousand years ago—though through form, not calculation.

The patio’s proportion, the wall’s height, the hallway’s direction… all were shaped to accompany the sun’s path.

It may sound technical, but it was deeply spatial. And deeply human.

Because light wasn’t something you turned on or off. It marked the hours, the rhythm, the use of space.

You sat in one place in the morning, another in the afternoon. Architecture didn’t dictate function. It suggested it—with light.

Photo: atrium of a Roman house (domus) in Pompeii, Italy, preserved after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD

What Have We Forgotten?

Today we open huge windows without a second thought. We orient living rooms without considering the winter sun. We trust double glazing as if it were magic.

But traditional Mediterranean houses—Roman, Greek, even Renaissance—didn’t need glass. They needed geometric intelligence.

And that, all too often, we forget.

This isn’t about going backwards. It’s about remembering that light can be structure—not just decoration.

In several of our projects, the central space of the house isn’t occupied by the living room or the kitchen. It’s occupied by nothing. A void. That sometimes fills with light, sometimes with shadow, sometimes with silence.

And that emptiness, more than any furniture, gives meaning to the rest.

When you sit there, even without understanding why, you feel you’re in the right place. No noise, no distraction. Just light entering, moving, fading.

And then you begin to understand that shadow is also architecture. Not only for what it hides—but for what it lets you guess.

You start to look at cultures that didn’t design from brightness, but from dimness. From shelter. From within.

From a more intimate relationship with light.

Photo: Benavites Tower Window, Valencia (Creative Commons)

The Islamic Tradition and Southern Iberia: Veiled Light, Shadow as Architecture

“Architecture born in extreme climates doesn’t seek direct light. It seeks to tame it.”

When we think of luminous architecture, we often imagine white, open spaces, endless windows, and cascading light. But that idea is recent—or rather, northern.

In hot climates—especially within the Islamic world—light is not pursued. Shade is.

And the light that is allowed in is the kind that has already learned how to behave.

Architecture That Protects

Walk through the historic quarters of Córdoba, Tetouan, or Granada and you’ll feel the difference: narrow alleys, blind façades, angled entrances. Nothing is revealed.

And yet, inside the houses, light is present. Not boldly, but quietly. Not as an optical phenomenon, but as an intimate atmosphere.

In the Andalusian home—rooted in Eastern traditions, but adapted to Iberian climate—light does not come from the outside. It comes from the centre.

A courtyard, a pool, a lattice screen. Architecture becomes a mechanism for filtering light and temperature—and in doing so, it creates beauty.

Moving Light, Permanent Shadow

In northern Morocco, I visited a 19th-century house in the medina of Chefchaouen. It was half-ruined, yet the central courtyard remained: a small fountain, a wooden gallery around it.

At midday, light entered through a single high window, bounced off the water, and scattered reflections across the whitewashed walls. There was no visible sky, no felt heat—only a floating glow.

It struck me deeply. A poor, unadorned space where light had clearly been choreographed.

Since then, every time I design a patio, I ask: how will the light move here at 3 pm in August? How will the air feel beneath this shade?

Photo: Casa de Zafra, Granada.

The Art of Filtering

One of the most refined—and most overlooked—elements of this tradition is the lattice screen.

In Al-Andalus, it was called ajimez or mashrabiya. More than decoration, it was climate and visual technology: letting you see without being seen, ventilate without exposure, illuminate without glare.

And it still works today.

In a recent project, we installed vertical wooden slats facing west. They didn’t mimic a specific form—but the principle was the same: block the harsh afternoon sun, let the grazing light through.

The result was a living room that became more beautiful as the sun dropped. A space that didn’t shine—it breathed.

The Courtyard as Total Interior

Walk through the historic quarters of Córdoba, Tetouan, or Granada and you’ll feel the difference: narrow alleys, blind façades, angled entrances. Nothing is revealed.

And yet, inside the houses, light is present. Not boldly, but quietly. Not as an optical phenomenon, but as an intimate atmosphere.

In the Andalusian home—rooted in Eastern traditions, but adapted to Iberian climate—light does not come from the outside. It comes from the centre.

A courtyard, a pool, a lattice screen. Architecture becomes a mechanism for filtering light and temperature—and in doing so, it creates beauty.

Photo: Alella Auditorium (Fem Arquitectura).

Time as Part of the Design

This architecture is not static. Light changes throughout the day—and space changes with it.

In the morning, the home faces its cool side. At noon, it retreats into depth. In the afternoon, golden light graces the courtyard and transforms colours.

It’s not only about avoiding heat. It’s about knowing how to live with light in all its phases.

This thinking—space shaped by time—is something I try to apply in all of our projects.

We should try not to design for handover photos. We must design for what it feels like to live there at 4 pm on a July day. Or on a Sunday in February, when light enters just through that opening no one was sure about—but now feels inevitable.

The Vernacular as Model

These houses, these courtyards, these ways of thinking about light, were not born in schools of architecture. They were born of necessity, of accumulated experience, of ingenuity passed on without drawings.

And yet, today they strike us as profoundly sophisticated.

Because they do not speak of style. They speak of climate, of a way of life, of a sensitivity to light that does not seek to tame the sun, but to live with it.

Perhaps that is why, when I work in places like La Selva, Empordà, or Garraf, I try to remember that the best reference is not always an iconic building, but an anonymous house that knew how to settle into the landscape, to open a window in the right spot, to close another that was unnecessary, and to let space breathe in shadow.

And once you have understood this, you begin to look differently at certain rural houses closer to home: the ones we find in villages, in the mountains, by the fields. Houses without pretension, yet full of intelligence.

Houses that, without knowing it, continue to converse with light as if it were a lifelong neighbor.

Photo: Masía Catalana Remodel (Fem Arquitectura).

The Modern Mediterranean: Light, Mass, and Shadow

“Light does not always break through. Sometimes it filters between thick walls, slips through a crack, rests on the floor for seconds. And that is enough.”

Looking again at the Mediterranean rural house with care —without condescension, without idealizing it— is one of the most productive gestures an architect can make.

There is no other model that has confronted climate, scarcity of means, and the passage of time with greater precision.

And its relationship with light is probably one of its most powerful lessons.

Shadow as Strategy, Not as Deficiency

If you walk through a Catalan masía in the interior of Girona, or a cortijo in the Vega of Granada, you will see compact houses, with thick walls and small windows. In appearance, dark. But in reality, they are machines of controlled light.

The Catalan masía, for example, never sought to admit “as much light as possible.” It sought only what was necessary: light that does not burn, light that does not tire, light that lasts.

Windows oriented east or northeast. The living room placed on the most protected side. The threshold as an intermediate space. Light did not flood in: it was carefully measured.

And that principle remains valid today.

Architecture of Mass and Thickness

In these dwellings, walls are not simple enclosures. They are thermal and luminous filters. A 60 cm dry stone wall not only insulates: it modulates the way sunlight enters.

Light projects itself on niches, on shelves, on the roughness of lime plaster.

In a recent project, restoring a village house near the coast, we decided not to open new windows. We simply cleaned the existing ones, slightly widened the interior sill, and let the plaster absorb the light with a minimal roughness.

The result was far more contemporary than any ventilated façade system.

And more human.

Photo: Cortijo San Francisco (Erlantz Biderbost).

The House as a Cave

In many places of southern Spain, the rural typology is closer to a cave than to a villa: excavated spaces, limewashed, oriented with brutal intelligence.

The cave-houses of Guadix, for example, are semi-buried structures that maintain a constant 18–20ºC year-round. But the most interesting aspect is not their thermal efficiency. It is how they treat light.

Light enters through a single frontal opening or through vertical shafts, allowing cross ventilation and diffuse zenithal illumination.

And that principle, applied today, still carries architectural potency.

The Exterior as Protector, Not Showcase

In the Mediterranean rural house, the exterior does not open ostentatiously. It protects.

Porches, eaves, pergolas… are not ornamental. They are regulators of light.

In summer, shadow is cast over the façade. In winter, when the sun is low, it enters just enough.

In the traditional houses of the Greek islands —such as those in Olympos (Karpathos) or the Cyclades— white is used as a natural reflector. Light does not enter directly. It bounces off courtyards, walls, and floors. Everything is illuminated without exposure.

Lateral Light, Deep Windows

Another essential characteristic: openings are deeply embedded in the wall.

A window is not a cut; it is a horizontal grotto. This creates a soft transition between interior and exterior, and projects elongated shadows that make the light that does enter even more valuable.

Italian architect Franca Helg, in her studies on rural architecture in Tuscany, spoke of “the window as narration of the landscape”: a thick frame, with a sill where one can sit, look out, wait.

The same occurs in many country houses in Mallorca or in Maresme.

It is a light of low horizon, horizontal, unhurried.

Photo: Masia Catalana Remodel (Fem Arquitectura).

Japan and Shadow: Another Way of Seeing Light

“In the West we seek clarity; in Japan, depth. There, light does not reveal: it suggests.”

For a long time, I wondered why certain Japanese houses felt so serene, even when they were almost empty. There is something in their silence, their tone, that goes beyond furniture or materials.

The answer, at least in part, lies in how they understand light. Or rather, in how they understand shadow.

Penumbra as Culture

Published in 1933, In Praise of Shadows by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki is a short essay that does not speak of architecture in technical terms, but with unusual aesthetic depth.

Tanizaki does not complain about the lack of light; he complains about its excess. How modernity —with its bulbs, its glare, its polished materials— destroyed nuance.

The traditional Japanese house is not illuminated. It is left in twilight.

The walls do not reflect: they absorb. The shōji paper does not let the sun pass through: it dissolves it.

“The gray nuance is what gives life to things. It is shadow that renders the object beautiful.”

— J. Tanizaki, 1933

Architecture of Thresholds

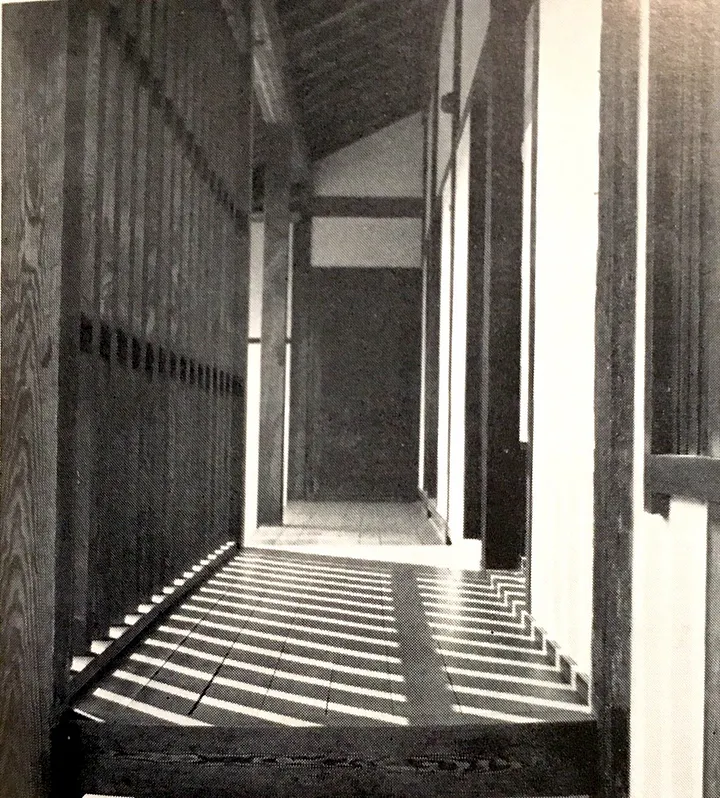

One of the most singular elements of Japanese architecture is the engawa: that intermediate gallery between inside and outside, neither courtyard nor room, neither street nor garden.

It is a strip of wood, covered, where light slips in laterally, filtered through the eaves.

And this space —so simple— defines the house much more than the living room or the kitchen.

It is where one reads, rests, and watches time pass.

I have tried to translate that idea into several projects. In one, we created a long porch, with a continuous built-in bench, sheltered by the roof overhang. Light did not enter frontally, but laterally. Months later, the client told us it was the place where they spent most of their time. Not because of what was there, but because of how it felt.

Photo source: Teiji Itoh, 1972

Materials That Absorb, Not Shine

Japanese plaster, rice paper, untreated wood… all these materials do nothing but absorb excess light.

In Japanese culture, light is not sought, it is suggested. Not directed, but allowed to flow.

And in that flow, something like calm emerges.

Interestingly, the materials we use in the Mediterranean —lime stucco, matte ceramics, terracotta— also handle light softly.

There is a subtle parallel between Japanese architecture and southern European vernacular: both prefer subtle vibration to direct glare.

The House as a Volume of Shadow

In Japanese tradition, the roof is not a technical plane: it is an artificial sky.

Large eaves, sloping roofs, deep galleries… all are designed to let light graze, not flood.

In Edo-period houses or in Kyoto villas such as Katsura, light enters only where it is allowed.

The rest is shadow, vibration, penumbra.

And that contrast turns every corner into a scene.

There is no theatrical control —as in Baroque architecture— but a kind of silent agreement with the sun.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto “Katsura Imperial Villa” (Rikuyosha, 2010)

The Vernacular as a Model

These homes, these patios, this way of thinking about light didn’t come from schools of architecture. They came from need, experience, wisdom passed on without drawings.

And yet, today, they feel profoundly sophisticated.

Because they don’t speak of style. They speak of climate, of a way of life, of a luminous sensitivity that doesn’t seek to dominate the sun—but to live alongside it.

Which is why, when working in places like La Selva, the Empordà or El Garraf, I try to remember: the best reference is not always a canonical building, but an anonymous house that knew how to settle into the landscape, open one window in the right place, close another, and let the space breathe in shadow.

And once you’ve understood that, you begin to see certain rural houses differently—those in mountain villages, near fields, without pretension but full of intelligence.

Homes that, without knowing it, still speak to the light like an old neighbour.

Knowledge Passed Without Books

These houses were not designed by any known author. Yet within them lies the wisdom of generations who lived with light, not against it.

And in a way, that is what inspires us most:

The use of honest materials, a direct response to climate, and an understanding that shadow is not a flaw, but a blessing.

Once you grasp this, you can look at Japanese architecture with new eyes.

Not as something distant or exotic, but as a parallel sensitivity.

Because in both worlds —that of the Catalan masía and that of the Japanese engawa— light is not celebrated as spectacle.

It is celebrated in stillness.

Photo: Riells del Fai Residence (Fem Arquitectura).